Designing Connected Terraform Modules with Minecraft Primitives

At Microsoft Ignite 2025, I introduced the latest version of the Minecraft Terraform Primitives module library — a set of Terraform modules designed to abstract and simplify the creation of geometric shapes in Minecraft. This library serves as a foundation for building increasingly complex structures by composing basic primitives, much like you would with LEGO bricks.

These modules not only make world-building in Minecraft more accessible, but they also offer a valuable learning pathway for newcomers to Terraform module development. Whether you’re a student, educator, or hobbyist, working with Minecraft provides a creative and engaging environment to explore Terraform’s functional domain-specific language: the HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL).

In this article, I’ll focus on one of the most useful shapes in the primitives library: the Cuboid module.

From Vectors to Volumes: Introducing the Cuboid Module

With the foundational vector module in place, we can now move beyond lines and begin building solid, three-dimensional objects. The Cuboid module is designed to represent a rectangular prism, defined by three dimensions — height, width, and depth — along with a direction and a material, just like blocks in Minecraft.

Here’s an example that places a 3×3×3 diamond cuboid in the Minecraft world:

module "diamond" {

source = "../../modules/cuboid"

material = "diamond_block"

direction = "east"

width = 3

depth = 3

height = 3

start_position = {

x = 486

y = 64

z = 142

}

}

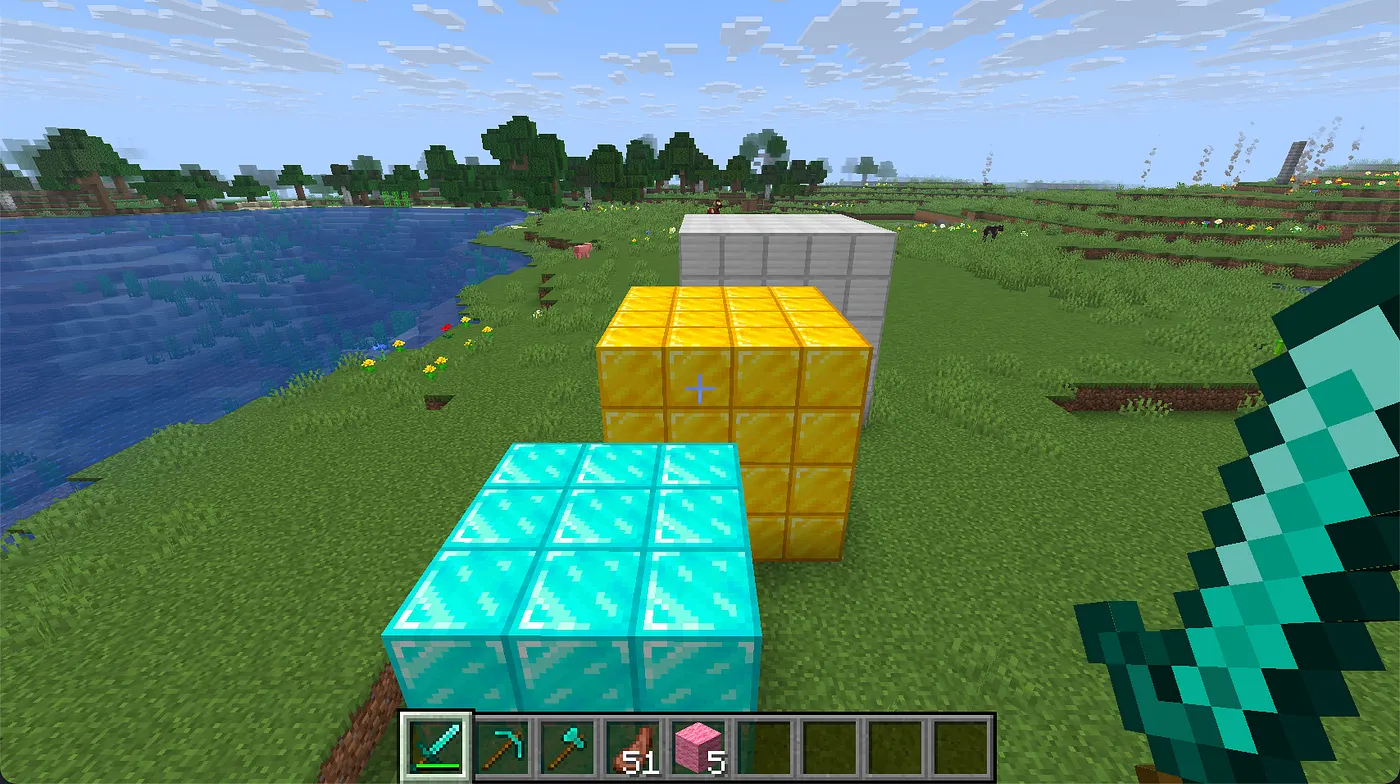

This is what the above code will produce in the Minecraft world.

When applied, this module generates a solid cube made of diamond blocks, facing east. The start_position defines the lower-back corner of the cuboid (depending on direction), serving as an anchor point for placement in the world.

Connecting Cuboids with Edges and Points

Just like the vector module, the cuboid module provides structured outputs to facilitate chaining and composition of multiple modules. Every cuboid includes 12 edges, each with 3 reference points: start, center, and end. This provides 36 potential connection points for building larger or more intricate structures.

Here’s an example output structure representing those edges:

{

bottom_north = { }

bottom_south = { }

bottom_east = { }

bottom_west = { }

top_north = { }

top_south = { }

top_east = { }

top_west = { }

vertical_north_east = { }

vertical_north_west = { }

vertical_south_east = { }

vertical_south_west = { }

}

Each edge contains:

{

start = { x, y, z }

center = { x, y, z }

end = { x, y, z }

}

These outputs make it easier to programmatically connect one cuboid to another — whether flush, offset, or overlapping — by referencing specific points of contact.

Building with Offsets: Gold and Iron Extensions

To demonstrate chaining, let’s add a second cuboid made of gold blocks. We’ll place this one just beyond the eastern edge of the diamond cuboid, starting from the center of the bottom_east edge and offsetting it slightly to avoid overlap:

module "gold" {

source = "../../modules/cuboid"

material = "gold_block"

direction = "east"

width = 4

depth = 4

height = 4

start_position = module.diamond.edges["bottom_east"].center

transform = {

x = 1 + 1

y = 0

z = 0

}

}

Here, the transform block applies an additional offset of 2 on the x-axis, which ensures the gold cuboid is not flush with the diamond block, leaving a one-block gap. If we only used an offset of 1, the two cuboids would touch edge-to-edge. This kind of subtle control is essential when planning structures with precision.

Next, let’s connect an iron cuboid to the gold one, again using the bottom_east.center as our reference point:

module "iron" {

source = "../../modules/cuboid"

material = "iron_block"

direction = "east"

width = 5

depth = 5

height = 5

start_position = module.gold.edges["bottom_east"].center

transform = {

x = 1 + 1

y = 0

z = 0

}

}

This time, we encounter an integer math issue. Because the gold cuboid has an even width (4), its center lies between two blocks. When using integer division, this effectively places the next cuboid starting from the second block, rather than the exact middle. As a result, alignment can appear slightly off depending on how you measure it.

Integer Division in Minecraft Geometry

The integer math issue described above is a subtle but important quirk of working with grid-based systems like Minecraft. When dimensions are even, the “center” technically falls between two blocks. Minecraft doesn’t support floating-point math in this context, so all positions are truncated to whole numbers.

As you would expect, this problem disappears when working with odd-numbered cuboids. Consider a copper cuboid with dimensions 5×5×5 — here, integer division correctly yields the central block as the midpoint, avoiding alignment issues.

By designing your modules with odd dimensions or factoring in alignment shifts manually through transform, you can preserve symmetry and improve visual coherence in your structures.

Conclusion

The Cuboid module in the Minecraft Terraform Primitives library offers more than just a convenient building block — it provides a gateway to learning core concepts in Terraform, such as input/output handling, modular design, coordinate systems, and functional programming through HCL.

By experimenting with cuboids and chaining them together using their exposed edges and calculated centers, users can gain hands-on experience with how Terraform modules interact. This approach can be especially effective for students, whether youth or adult learners, providing a fun and tangible way to engage with abstract programming concepts.

As the primitives library continues to evolve, I hope it inspires more builders, educators, and learners to explore what’s possible with Terraform — and with Minecraft.