Designing Cohesive Infrastructure Modules: Understanding Dependencies and References

When architecting infrastructure on Azure, particularly with Azure Front Door as the entry point, understanding how different components depend on each other is essential — not just for initial provisioning but also for long-term operational stability.

A common point of confusion arises when evaluating the relationships between the front-end load balancer and the services it routes to. It’s important to clarify that while there appears to be a dependency chain from Azure Front Door to downstream components like Azure Functions or AKS clusters, the relationship is not a hard dependency in the traditional sense.

Azure Front Door and Route Configuration Context

Azure Front Door acts as a global, front-end load balancer. Its primary role is to route client traffic to the appropriate backend services, known as “origins.” These origins might be hosted in App Service Plans, AKS clusters, or other compute environments that reside within your core or shared infrastructure.

The critical insight here is that the configuration of routes and their associated origin groups within Front Door should be treated as a tightly coupled set. Maintaining both together ensures visibility into the entire routing landscape and enables informed decision-making about how traffic flows are designed and maintained. This contextual integrity is vital for creating a maintainable and scalable architecture.

Misconception of Downstream Dependencies

It’s easy to assume that Azure Front Door has a downstream dependency on the services it routes to. However, this assumption is misleading. The load balancer doesn’t require the origins to be operational at the time of its deployment. In fact, one of its key features is origin health monitoring — it doesn’t rely on the existence of a healthy endpoint; it reports whether or not one is available. This is a subtle but important distinction.

By design, Front Door is intended to operate independently of the health of its origins. Its responsibility is to observe and report the state of those origins, not to depend on them. This means that during the early phases of infrastructure deployment — what we might call “Day 1 operations” — Front Door can be provisioned alongside other shared infrastructure components, even though the actual workloads it will route to may not yet exist.

Understanding Dependency Types in Azure Infrastructure

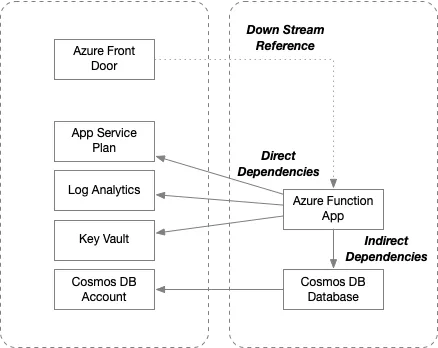

When building and organizing infrastructure as code, especially with Azure services like Azure Functions, App Service Plans, Cosmos DB, Key Vault, and Azure Front Door, it’s important to understand the nature of dependencies between components. These dependencies impact how infrastructure modules are designed, how services are deployed, and how failures or delays in provisioning one resource may affect others. Below are four key dependency types that help clarify the nuances of Azure-based architectures.

- Direct Dependencies

A direct dependency exists when one component explicitly depends on another and references it within its deployment module. For example, an Azure Function that depends on an App Service Plan is a classic case of a direct dependency. The function app must be deployed within a specific plan, and its infrastructure code will include an explicit reference to that plan. If the App Service Plan isn’t available or correctly provisioned, the function app itself cannot be created. These are hard dependencies, meaning they are both required and enforced during deployment.

- Indirect Dependencies

An indirect dependency occurs when a component relies on another service, but not through a direct reference. Instead, the dependency is introduced by a sub-component or nested resource that is deployed as part of the module. For instance, suppose an Azure Function’s module provisions a Cosmos DB database to store application data. The database must live within a Cosmos DB account, and that account might be provided by a shared infrastructure module. In this case, the function app doesn’t reference the Cosmos DB account directly, but the deployment of a resource within its module does. This creates an indirect dependency on the Cosmos DB account, which is downstream but shared.

- Soft Dependencies

A soft dependency is a non-blocking reference to another resource. The dependent component can still be provisioned even if the referenced resource is unavailable or incomplete. An example is an Azure Function configured to use a Key Vault reference in its app settings to load a secret. If the secret is missing or hasn’t yet been provisioned, the function app can still deploy successfully. The secret simply won’t resolve at runtime, which may cause the application to malfunction but will not halt the deployment process. Soft dependencies are typically used when configuration values may lag behind the infrastructure.

- Upstream References

An upstream reference is when a higher-level component, such as Azure Front Door, references a service that resides in a different module or layer, without creating a hard dependency on it. For example, Front Door might route traffic to an Azure Function. While the function app itself may have hard dependencies on core infrastructure like a shared App Service Plan or Key Vault, Azure Front Door does not. It simply holds a reference to the function’s endpoint. If the function app isn’t provisioned or is unhealthy, Front Door can still be created and will report the origin as unhealthy. It doesn’t fail because the function is unavailable — this makes it a reference, not a dependency. This distinction is key to avoiding circular dependencies in modular infrastructure designs.

Sequencing Deployments: Day 1 Ops and Beyond

Let’s consider a standard deployment flow. During Day 1 Operations, shared infrastructure is provisioned. This includes foundational components such as monitoring stacks, networking, identity management layers, and yes, Azure Front Door itself. At this stage, the origins configured in Front Door will likely report as unhealthy or unavailable. This is expected and entirely appropriate — they simply haven’t been deployed yet.

The next phase involves provisioning the workloads that rely on the shared infrastructure. In your team’s case, these are Azure Functions. These workloads have a dependency on the core infrastructure laid out in the earlier phase. As each function app spins up and becomes available at a defined endpoint, the origins in Front Door, assuming they were pre-configured correctly, will transition from unhealthy to healthy status.

This sequencing allows for a clean separation of concerns. The infrastructure provisioning pipeline can lay the foundation without being blocked by the status of downstream services. Meanwhile, the configuration of Azure Front Door anticipates future workloads, ensuring a seamless transition as components come online.

Conclusion

By decoupling the conceptual dependency between Azure Front Door and its origins, teams can simplify their infrastructure deployments and reduce unnecessary coupling in their provisioning logic. Front Door’s role is to route and monitor, not to depend. When configured with the full context of the routing and origin groups, and when deployed as part of shared infrastructure, it provides a resilient and flexible architecture that gracefully supports the eventual rollout of downstream services.

Understanding and embracing this model enables better modularization, clearer responsibilities across teams, and a more robust deployment process that scales with complexity over time.